In the 1940’s doctors discovered a radical new treatment for patients with severe, life-threatening epileptic seizures. This procedure involved cutting the corpus callosum, a thick bundle of nerve fibers that acts as a bridge between the left and right sides of the brain.

Seizures start in one hemisphere, and quickly spread across the brain, causing a full-body convulsion. A neurosurgeon named William Van Wagenen believed that by severing this connection between the left and right hemispheres, he could contain the seizures within one side, reducing the severity of the attack.

This surgery was successful in reducing seizures, and by the 1960s, these corpus callosotomies were becoming more commonplace. But doctors started to notice some astonishing side effects that would change neuroscience forever!

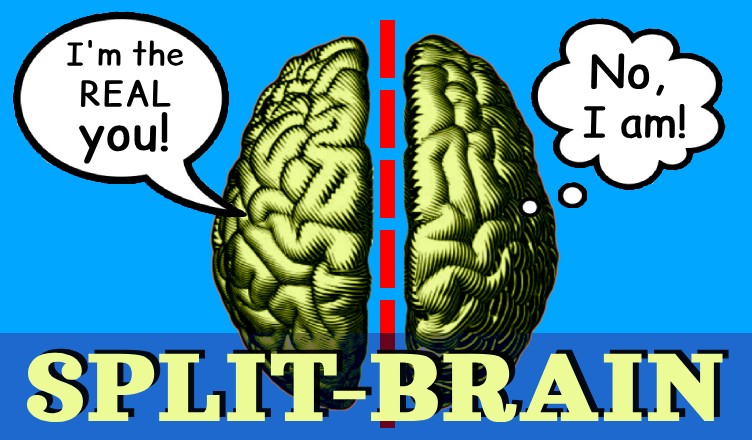

One body, two minds!

Once cut off from each other, it was like the patient had two separate minds occupying the same body! The left brain controls the right side of the body, as well as language, logical thinking, mathematics and problem-solving. While the right brain controls the left side of the body, as well as emotional expression, tone, facial recognition, understanding maps, art and music, and “big-picture” thinking. But both operate as independent entities, seemly unaware of each other!

Neuroscientist Roger Sperry was conducting split-brain experiments in cats and monkeys when he observed that after the procedure, each hemisphere could learn things separately. This made him wonder if the same could be true for humans. He teamed up with Michael Gazzaniga, a graduate student working under him at the time, to study how the two hemispheres of the brain communicate, and what happens when that connection is severed.

They carried out numerous experiments and observations on patients who had undergone corpus callosotomies, such as showing them images in only one eye, or asking them a question in only one ear.

When shown an image in the right eye, (connected to the left brain, controlling language), the patient is able to accurately describe what they see. But when shown only to the left eye, (connected to the non-verbal right brain), the patient could not describe what they had seen, but could point to it with their left hand, or draw it! Their right hemisphere knew information that their left hemisphere was unaware of!

In another experiment, patients were handed an object in only their left hand, (controlled by non-verbal right brain), while blindfolded. Afterwards, when asked what they were holding, they couldn’t say, but their left hand could point to the object in a group of items!

The right hemisphere also experienced independent emotions. When shown a disturbing or violent image to the right hemisphere only, the patient would look uneasy or nervous but couldn’t explain the reaction. When asked, they would simply make something up. Even though the right hemisphere is unable to speak, it can understand speech, follow instructions and answer yes/no questions using gestures!

It was concluded that both hemispheres were acting independently, had different thoughts, and would even make different choices. When asked to pick out what shirt to wear, the right hand might reach for a smart shirt, (the more logical choice), while the left hand might reach for something more flamboyant or expressive.

In extreme cases, this even lead to “Alien Hand Syndrome“, where the patient is unable to a control their left hand; repeatedly unbuttoning their shirt while their right hand tries to buttoning it back up, or even slapping them without their control!

However, patients were not aware of their separate identities, and did not feel like “two people”. In every case, the left hemisphere, with it’s control of language, logical thought and internal narration, would rationalise the behaviour. Their left brain filled in the gaps so well that they didn’t perceive the split, and believed they were acting as a single, unified self.

The Left Hemisphere Confabulation Test

Another interesting finding was the Left Hemisphere Confabulation Test. Researchers would flash a different image to each eye, a chicken claw to the verbal Left Brain and a snowy scene to the non-verbal Right Brain. The patient would see the chicken claw, but when asked to choose between a shovel and a chicken with their left hand, they would pick up the shovel. However, when asked why they had chosen the shovel over the chicken, instead of looking confused, the Left Brain would immediately start to confabulate to make sense of the situation; the shovel is for cleaning up after the chickens!

This shows us how our left hemisphere prioritizes coherence over accuracy—when it lacks information, it automatically invents logical-sounding explanations rather than admitting uncertainty. It explains how we tend to rationalise an instinctive decision after the fact to make it seem conscious and deliberate, when really we acted first and thought later.

Split-brain research reveals that the brain is not a single, unified entity, but rather a collection of systems working together. It shows that our left hemisphere is constantly storytelling, constructing a narrative, sometimes inventing explanations that don’t even reflect reality. But what does it mean for our understanding of consciousness itself when it can be cut into two with a knife? Are both hemispheres still part of a single self, despite having independent thoughts and emotions, or have they become two separate entities—sharing a body but unaware of each other’s existence?

Parallels Between the Brain and Agentic AI

To me, these findings bear a striking similarity to the current, agentic approach to artificial intelligence. In agentic AI a network is made up of multiple independent agents (small, specialised programs), each focused on one particular task. One might handle language processing, another image recognition. There could be agents for memory, decision-making, emotion, creativity, spatial awareness, etc. And one overarching agent (sometimes called an Orchestrator) that receives the request and decides how to delegate it among the specialised agents. The Orchestrator then integrates the responses from the various agents and stitches everything together into one single, coherent response.

Much like an AI Orchestrator, the left hemisphere receives input from our various senses, (sight, sound, touch), etc, hands tasks off to the various “agents”, (visual cortex, auditory cortex, limbic system, motor cortex, prefrontal cortex, etc.), then constructs a unified experience by stitching the responses together into a single narrative.

But if consciousness can be divided in two, then perhaps what we think of as “the self” is nothing more than a useful illusion, held together by the brain’s ability to tell stories.